We’ve come to upper Provence, primarily to visit Alexandra David Néel’s house in Digne-les-Bains. If I’d been paying attention, this would have long been marked on my calendar. It’s the 100th anniversary of her trek into Tibet. Auspicious.

I have declared Alexandra David Néel to be my patron saint. I nominate her saint of all women of a certain age who dream of escape. She was born near Paris, in 1868. She ran away early and often. Her era didn’t allow such things of women. The only ambition you were allowed to have was that of a respectable marriage and children. But Alexandra was an anarchist, free-thinker, early western Buddhist, and very early feminist. She became an opera singer at a time when that was quite disrespectable, which made her unsuitable for an honorable, conventional marriage. Fine by her. She sang with a touring company in French Indonesia, then in Tunisia, where she met Philippe Néel, whom she would marry at 36. She stuck around playing wife for 7 years; 7 years of neurathenia, as they called it, aka depression. In 1911, at 43 years old, she left. She returned to Asia to study Sanskrit. Though she initially planned to be gone for a year and a half, she stayed away for 14. Away suited her well. She thrived.

She met the 13th Dalai Lama, who advised her to learn Tibetan, met Buddhist teachers and even did the whole hermit-in-a-cave thing, learning esoteric practices. She became a well-known orientalist and an expert in Buddhism, publishing ethnographic articles for newspapers and magazines, which is how she earned a living. Early biographers said it was her husband who financed her travels. They were wrong. She did need his help however. Not financially, but practically. Women were not allowed to have bank accounts. She couldn’t touch her money without him.

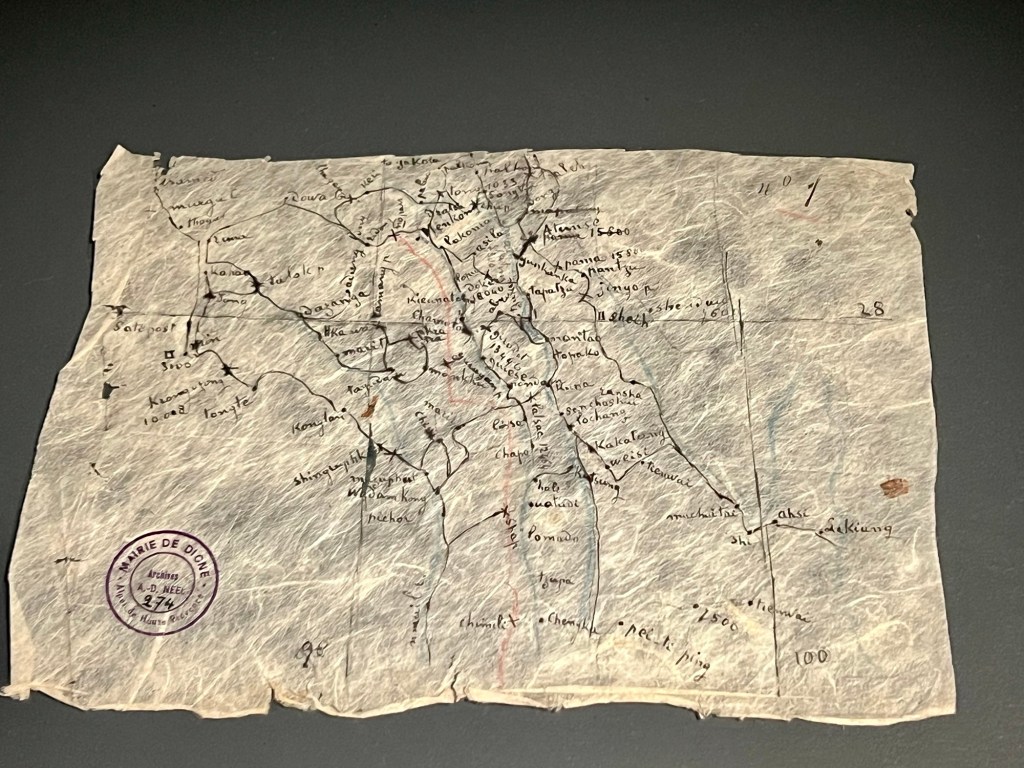

Alexandra became world famous with the publication of her book, Voyage d’une Parisienne à Lhassa, a page-turning, best-selling account of how she became the first white woman to reach the forbidden city of Lhassa, in Tibet. A French friend saw me reading it and commented that he thought she was rather full of herself. I replied that if I’d done what she did, you would never hear the end of it. She trekked 2,000 kilometers across the Himalayas, in winter, at night to escape detection. At 55 years old. In 1923-24. And it goes without saying, without space-age fabrics and equipment. She was accompanied by a 25 year old servant, Lama Yongen, who had been in her employment since the age of 13. She later adopted him.

After her return to France in 1925, she bought the house in Provence. Alexandra and Philippe would never live together again, though they stayed married and in almost constant contact through letters. She returned again to Asia, in 1937, in time to get caught in the middle of the second Sino-Japan war. Fleeing the conflict, she found herself stuck in Tibet for 5 years while Europe had its own second round of insanity. She finally returned in 1946 and settled back down in Digne, spending long days writing books, letters, studies on the Tibetan language, and cultivating her mystique, which allowed her to sell enough books to stay independent.

The house was a lovely, low-ceilinged arts and crafts number, with lots of windows. Her collection of rare Buddhist texts and museum-worthy statues are no longer there, they’re in the Guimet museum in Paris, the place where she first discovered Buddhism, and dare I be so clichéd as to say, her destiny? Her own relics are there, in place. Her pen, tea set, toiletry kit. The homeopathic vials she carted with her on her travels. I might find religious relics silly, but I found it touching to look at a box of pen nibs that she had.

She died at home in 1969, at nearly 101 years old, after having renewed her passport the year before. Life goals.

I think of her often when I’m cold, or hungry, or tired, or lost, or all at the same time; even if I’ll never be in the Himalayas or reduced to eating shoe leather in a cave. It puts a little perspective on my deprivations. I still like to think, what would Alexandra do? Not whine about it, that’s for sure, as I am sometimes wont to do. She would keep going.

Onward !

Maer